1971: Remembering the story of Upper Ouse Navigation 1790-1868

- Dec 23, 2025

- 4 min read

A River with Big Ambitions: The Story of the Upper Ouse Navigation

Taken from: The Sussex Industrial History Archive Volume 1

In the late 1700s, Sussex was a quiet, rural place. Farming dominated the landscape, roads were often little more than muddy tracks, and heavy industry barely existed. But this was also an age of confidence and innovation. Across Britain, people were straightening rivers and digging canals, convinced that better transport would bring prosperity. Sussex was no exception.

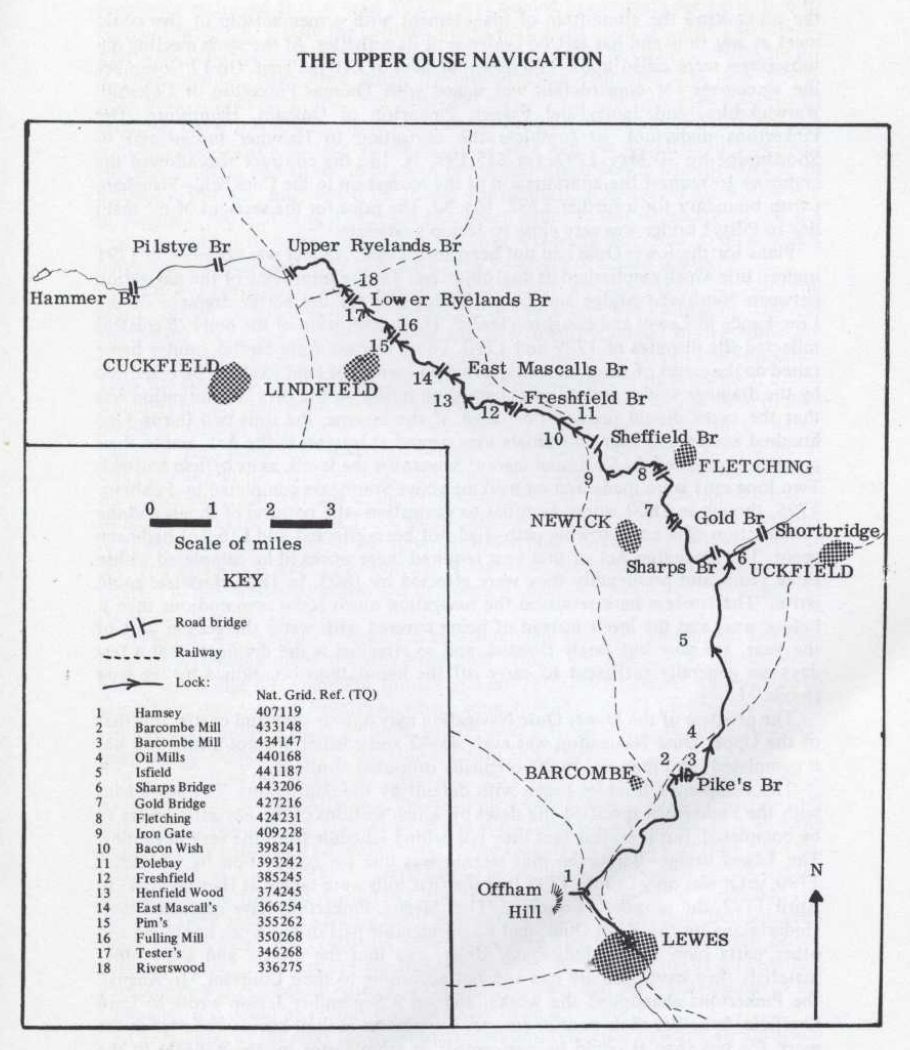

Four rivers run roughly parallel through the county – the Arun, Adur, Rother and Ouse – and all were seen as opportunities. If barges could replace carts, goods could move more cheaply and reliably. The River Ouse, flowing from the Weald down to the sea at Newhaven, became one of the most ambitious of these projects. Though it looks modest today, it was once engineered to carry barges more than twenty miles inland.

A working river before canals

The Ouse was already being used long before formal improvements began. As early as Tudor times, iron from the Weald was floated downstream, and by the early 1700s boats could reach surprisingly far upstream. But this was a fragile system. Floods, droughts and shifting channels made navigation unreliable, and by 1790 barges could go no further than Barcombe Mill, just four miles above Lewes.

Things changed in the late eighteenth century. Successful canal schemes in the Midlands made landowners elsewhere eager to follow suit. The Ouse seemed promising: it linked the clay soils of the Weald – hungry for fertiliser – with the chalk downs, rich in lime. Some enthusiasts even dreamed of reviving Sussex’s wool and iron trades through better transport.

Big plans and bold promises

The driving force behind the scheme included influential local figures such as Thomas Pelham of Stanmer Park and Lord Sheffield, one of the county’s largest landowners.

They brought in William Jessop, one of the country’s top engineers, who produced an ambitious plan in 1788: deepen and straighten the river, build dozens of locks, and make it navigable for 30-ton barges far into mid-Sussex.

An Act of Parliament followed in 1790, creating the Upper Ouse Navigation Company. It could raise £25,000 in shares, charge tolls, and build locks, wharves and side cuts. A separate authority would improve the lower river and deal with drainage near Lewes. On paper, everything looked set for success.

When things start to go wrong

Work began quickly, but problems appeared almost at once. Contractors known as the Pinkerton brothers were hired to build much of the navigation. They fell behind schedule, produced shoddy work, and eventually walked away. By then, most of the money had already been spent.

The company made a crucial mistake early on: instead of finishing one complete stretch and earning tolls, it spread work along almost the whole length of the river. The result was half-finished cuts, incomplete locks, and landowners irritated by disruption with no benefits to show for it. Debts piled up, loans were taken out, and creditors became increasingly impatient.

Progress limped forward over the next two decades. Barges reached Sheffield Bridge by 1793, Freshfield around 1805, and Lindfield in 1809. The navigation finally opened to its furthest point, near Upper Ryelands Bridge, in 1812 – more than twenty years after the first Act, and still short of where it was meant to end.

By then, the company was heavily in debt and paying neither dividends nor interest.

What actually moved on the river?

Despite all this, the Upper Ouse did real, useful work. Chalk and lime were its lifeblood, helping farmers improve heavy Wealden soils. Coal was just as important. Shipped into Newhaven and then carried upriver, it made fuel far cheaper for inland villages such as Lindfield, Fletching and Uckfield.

Barges also carried timber, gravel for roads, farm produce and bark for tanning. By 1801 there were nearly forty barges working the river, most owned by families in Lewes. The Hillman family, in particular, dominated trade on the upper reaches.

Lewes itself became a small centre for barge and ship building, using high-quality Wealden oak. For a time, the river supported a whole web of local trades and livelihoods.

But it was never a goldmine. The countryside was thinly populated, industry was limited, and Sussex iron was already in decline. The navigation survived, but it never really prospered.

Beaten by the railways

The final blow came from the railways. The London–Brighton line opened in 1841, followed by routes to Lewes, Newhaven and later Uckfield. At first the navigation even benefited, carrying materials for railway construction. But it couldn’t compete for long.

Tolls were repeatedly cut, wages reduced, and maintenance postponed. Locks fell into disrepair. By the late 1850s barges could no longer travel above Lindfield, and by 1868 even the lower locks had effectively closed.

This was a familiar story across southern England: agricultural waterways that struggled on for decades, only to be quietly pushed aside by faster, more flexible rail transport.

A quiet river, a busy past

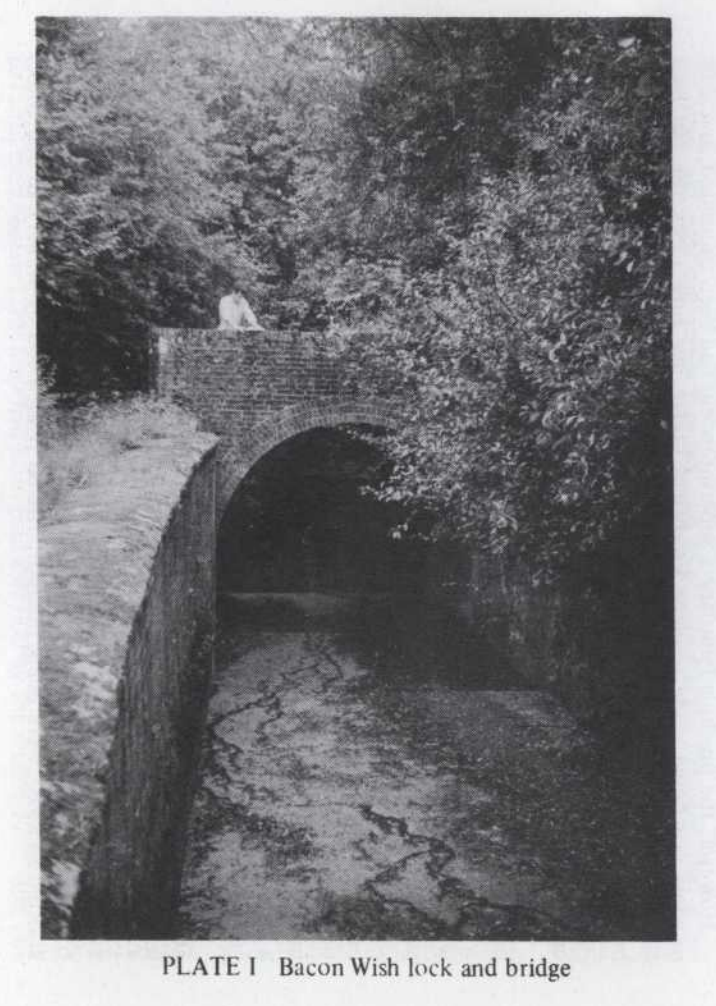

Today the Upper Ouse is peaceful again. But its past is still visible if you know where to look – in straightened channels, overgrown locks, old wharves turned into cottages, and curious bends in footpaths and fields. For a brief moment, this modest river carried grand hopes of improvement and prosperity. In the end, it was overtaken not by failure of effort, but by the sheer speed of change.

Comments