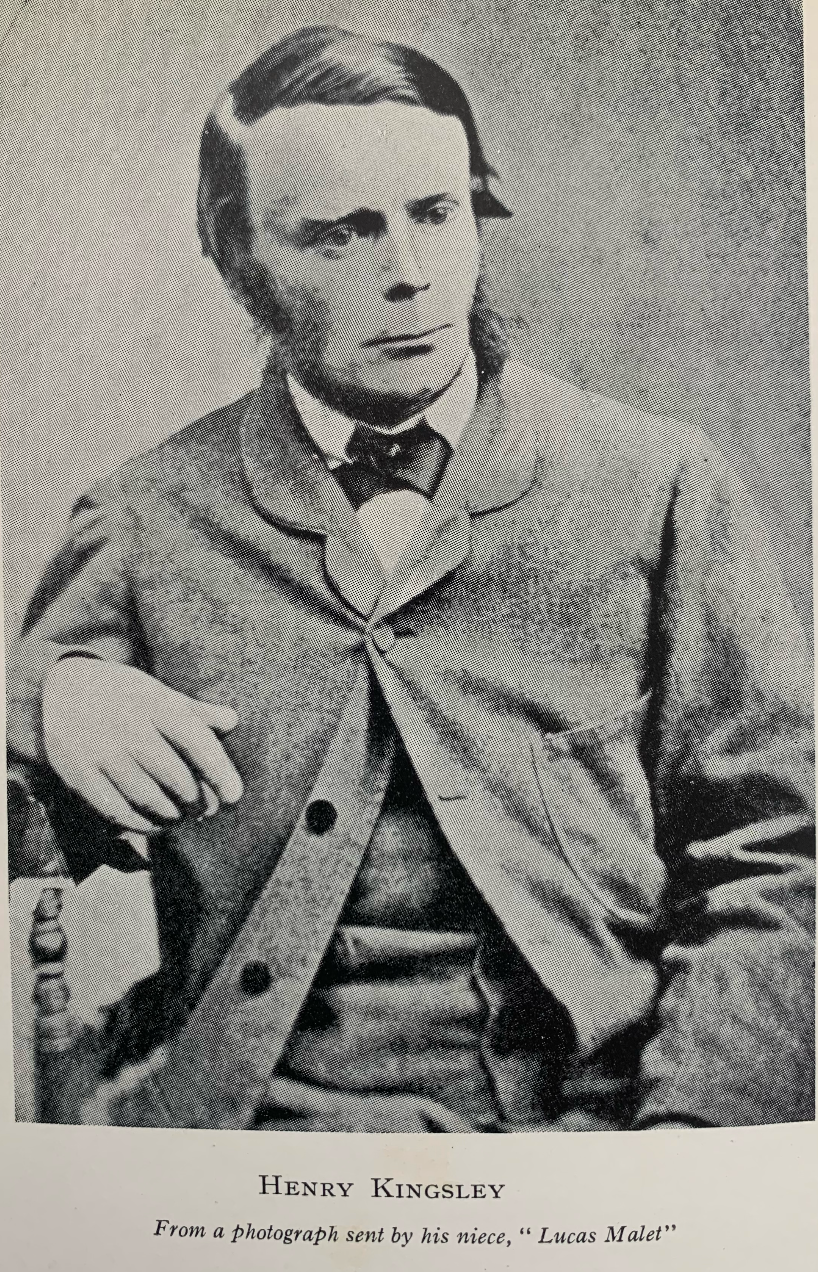

1931: The last days of a great writer - Henry Kingsley in Cuckfield

- andyrevell

- Aug 8, 2025

- 8 min read

From ‘Henry Kingsley 1830-1870’ by S.M.Ellis 1931

CUCKFIELD

WHEN the doctors broke the dread news to Henry Kingsley that he was a dying man and that he could only anticipate a few more months of life, he resolved to leave London and spend his last days in the country amid scenes of pastoral beauty such as had ever called to him since his earliest youth. Accordingly towards the close of 1874 he and his wife removed to the village of Cuckfield, in the Weald of Sussex. They rented a very ancient and picturesque cottage, timbered and gabled, low-ceiled and with leaded, latticed windows, called "The Attrees”- after the old Sussex family of that name, for some of the Attrees were living in the house in 1681. Here Kingsley led a retired and quiet life. He cared to know very few people locally, and to his neighbours he appeared pre-occupied and wrapped in thought, a sad and shy man who, naturally, in view of his mortal illness, had no desire for society and casual conversation, though when he did speak he was always courteous and agreeable. There are several persons still living who remember Henry Kingsley in Cuckfield, and they all agree in saying that there is not the slightest truth in the allegation that he was addicted to drinking or in the totally unfounded statement that he and his wife were socially ostracised in the village. On the contrary, a former inhabitant, Miss E. M. Waugh, writes, (1) "We were very proud to have them amongst us, and I know many kind things were done to make life easier for them. Henry Kingsley was an intensely shy man, and that, together with their straitened means and his health, naturally made him lead the life of a recluse. Mrs. Henry Kingsley was a remarkable woman and clever. Her views were certainly much in advance of her time.” (2)

As he trod the steps of his Via Dolorosa, Henry Kingsley found consolation in religion, for he had always preserved the piety of his early upbringing. The Reverend Henry Hollingworth, who was curate of Cuckfield, 1865-1876, states:

"Like all Cuckfieldians I saw little of Henry Kingsley. He used to go (I think every Sunday) to early Communion, but otherwise was mostly indoors. I think that he died of cancer of the tongue, and I believe that I gave him his last Communion. He was not at all well off when at Cuckfield when he wrote Fireside Studies. I remember that he had a great dislike for Queen Elizabeth, of whom he once said to me that she had all the vices of her sex except unchastity.”

So the old quaint humour flashed out now and again. But these last days appear superlatively sad and grievous, for he was almost entirely shut up in the low-pitched, dark rooms of the cottage, suffering all the anguish, physical and mental, of the most horrible of diseases, and only going out of doors for the short walk to the church for his Communion. But here, as he left the building, his eyes were unfailingly refreshed, for as an artist of the beautiful he must have truly loved that most exquisite of views which is obtained from the churchyard of Cuckfield- away across the woods and pastures of the last champaign of the weald to the long and noble sweep of the downs- “Along the sky the line of the downs, so noble and so bare," with its high lights and fleeting shadows. Would that Henry Kingsley had crystallised into literary form the fair scene in one of those snatches of melodious prose which were his peculiar gift for conveying the beauty he saw to the eye of another far removed from him in time or place. But the supreme strings of his lyre were now broken, and he could sing no more in the rich, flowing, colourful phrases of yore, (3) He did, however, give a charming glimpse of his surroundIngs in one of the last things he wrote, a paper entitled Two Old Sussex Worthies:

“On the rib which divided the infant Adur from the infant Ouse stands Cuckfield, from the hill above which you can see sixty miles, south, south-west, and south-east; or turning back, and looking northwards, you can see St. Leonards, Tilgate, and Ashdown forests, hanging like a purple cloud with gold and green openings. It is supposed to be the healthiest town in England. Coming to the summit of the steep little street, on the old London Road, the traveller sees the pearl-grey wall of the downs, cut almost to the zenith by the tall spire of the church.

Reaching the churchyard he finds that he is at the edge of vast thickly-wooded valley, about nine miles broad, bounded on the further side by the long, high mass of the downs far to the left is the back of Beachy Head, far to the right the hills beyond Chichester. The church is one of the most beautiful in England, cared for like a jewel, and the wondrous old houses abutting into it would

be highly remarkable elsewhere. In short, there are few places like Cuckfield churchyard; but still more remarkable than church or churchyard is Cuckfield Place close by, with the finest lime avenue of its length in England, its Tudor house, and its deer park most artistically broken

into glade and lawn, the dearly loved haunt of Shelley, and the origin of the Rookwood of Harrison Ainsworth.”

This article appeared in a volume of papers entitled Fireside Studies, 1876, and in the same year of his death was published Henry Kingsley's last novel, The Grange Garden, the scene of which was suggested by the garden of Cuckfield Place or of some other old house in the neighbourhood. The sun is setting and the shadows lengthen. The last glimpse of Henry Kingsley is again from the pen of Miss Thackeray. She heard from Leslie Stephen that their friend was very ill, so they arranged to go down together to Cuckfield and see him :

“We walked from the station along a village road with trees on either side to a sort of low farmhouse cottage, where the Kingsleys were then staying. Mrs. Kingsley was Iying down upstairs; he was alone to receive us in the latticed sitting-room. He was himself and yet different

from himself; his eager manner was gone; he was very gentle, but he seemed collected and cheerful only. “They tell me I am going to die,” he said. “I can't believe it, I don't feel like a dying man.” He said this quite naturally, with a sort of simplicity and courage which were a part of

all his life. He went on to talk of books and every-day things. He seemed pleased that we should have come to see him, and made us ashamed by making so much of it. Very soon afterwards we heard that he was gone.”

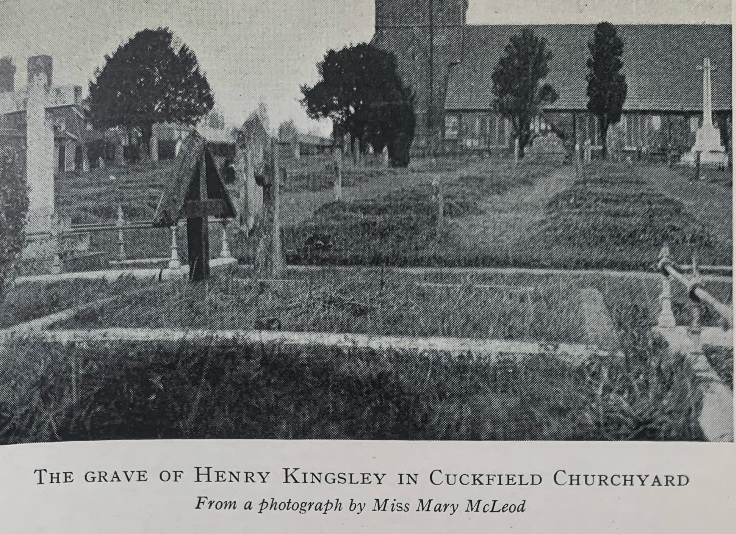

Henry Kingsley died on May 24th, 1876, in the spring and blossom time he had loved so well in his brief days of happiness and joy. He was buried in the churchyard of Cuckfield, not obscurely as some have imagined, but with the attendance of a large number of friends and villagers. The vicar and his two curates took the service, and Mr. Malcolm Lawson, organist of Chelsea Apostolic Church was at the organ. Cuckfield Church seems to have adopted a picturesque ritual at this date, for the choir wore violet cassocks at the funeral, and the pall on Henry Kingsley's coffin was also violet in colour, with the words, worked in white, "The Lord Preserveth the Souls of His Saints. He shall make their Darkness to be Light." All the mourners carried sprays of lilies-of-the-valley, and these were thrown into the grave at the close of the service, while two wreaths of lilies were placed there by Mrs. Kingsley. The novelist's only surviving brother, Doctor George Kingsley, and his wife, were present; also Mr. Eversley and his niece, Miss Murray-Alen (cousins of Kingsley on his mother's side); Mr. George Lillie Craik (husband of Miss Mulock), representing his publishers and good friends, the Macmillans; Mr. Edwin Waugh, the Lancashire author (4) together with other friends. Over the grave now stands a low wooden cross bearing the words, Entered into rest on the Vigil of the Ascension, May the 24th, 1876, Henry Kingsley, aged 46 years. R.I.P," and the text, " In Thy Presence is the Fullness of Joy.” (5)

There he rests in English soil, as he would choose, and around him the fair Sussex landscape. I venture to submit that no cloud darkens his memory save the transitory and excusable one of financial difficulties : in the literary firmament his name shines high, sparkling, and clear.

(1) In The Sussex County Magazine, April, 1930.

(2) Sarah Kingsley was of literary tastes, for in 1879 she "edited" a novel entitled Dead Leaves, by Cecil Haselwood, which was her maiden surname. She was also a good reciter, and is still remembered in Cuckfield as taking part in Penny Readings, so popular in Victorian days, and giving a fine recitation of The Wreck of the Hesperus. It is to be feared that she was left very badly off after her husband's death: Henry Kingsley's estate was valued only at £450 when his will was proved. Over thirty years later efforts were made to obtain for her a grant from the Royal Literary Fund, for in a letter to Ms Sigand dated June 11th, 1907, George Meredith wrote: “The presentation of the sad case of the widow, coming from you, as a member of the Society, direct to the Secretary, may have a better effect. Write it fully, but plainly. Henry Kingsley has a claim on our literature. A pension, I fear, is precluded by the rules. A donation there may be well. Write immediately. You can, if you please, say what I think H. Kingsley”.

Mrs Kingsley made many applications both to public men and Societies for monetary assistance, so inadequate are the public funds available for the relief of literary men and their dependants in this country. Despite her troubles and poverty, Mrs Kingsley preserved her forceful and assertive character to the end, and was an active worker for temperance and other social causes. In her last years at Folkestone according to local report, her behaviour was eccentric and often antagonistic to the townspeople. At some previous period she had livd at 2, Old Elvet, Durham, and Hythe. `she died at No.7, The Bayle, Folkestone, on August 12th 1922, at the age of eighty, thus surviving her husband by forty six years.

(3) Yet is he at the last poignant as a murdered bird, so proud were S he gleaming wings now crushed and faded," as Mr. Michael Sadlier so finely expressed it in his critical appraisement of Henry Kingsley in The Times Literary Supplement of January 2nd, I930 (reprinted in part from a longer paper in The Edinburgh Review, October, 1924).

(4) Possibly it was Edwin Waugh who wrote the pleasant tribute to Henry Kingsley in The Sussex Daily News of May 26th, 1876, wherein he was described as a man of high culture, with a vast amount of general information, an excellent conversationalist who flavoured his talk with a quaint, eccentric humour that rendered personal intercourse extremely pleasant - “a fair, frank, hearty man, pleasant to look upon, always kind, cheery, helpful and hopeful. Though he was a

middle-aged man in years, yet he had a boy's pure, fresh, generous heart. He was ever ready to help and encourage his younger and less successful brethren in the republic of letters, and by many of them his loss will be felt as an irreparable bereavement."

(5) It is intended this year, 1931, to place over the grave of Henry Kingsley a memorial stone, a tribute from admirers of his work.

Comments